The holy month of Ramadan begins on 23 March. So, it is a perfect occasion to ponder about the way religious tolerance functions (or mis-functions) in Bali. I am using these two words because it is part of conventional wisdom – or rather of conventional politics —to assess that religious tolerance is a given reality. As if tolerance were part of a Balinese ‘essence’ and, as such, did not have to be fought for.

The main religions of Bali, Hinduism and Islam, do have their respective concept of tolerance, and when talking about the relations between their respecting following in Bali, the clerics of both sides will not fail to boast about it: “Your religion is your religion, my religion is my religion”, will say the Moslem clerics, mentioning a verse from the Holy Koran. “What matters is not the Truth, which is unknowable, but the quality of one’s karma (deeds)”, will retort the Hindu holy man. Thus, tolerance is indeed part of the teachings of the two religions.

Tolerance is also rooted in the island’s history: in the pre-colonial period, most Balinese kingdoms were defended by Moslem mercenaries, whose descendants now live in kampongs (hamlets) usually located in the immediate vicinity of the royal palaces. So it is not rare in Bali to find Moslem communities linked by tradition to noble families and associated to the religious paraphernalia of some of their ceremonies.

Inter-marriages also took place without this being a big issue between the two groups. The Hindu-Balinese and Moslem Balinese were in fact intermingled to such an extent that religion was at best a secondary aspect of their identity; henceforth conflicts almost never took a religious colouring. In spite of demographic changes due to migratory movements, this situation remained basically unchanged until very recently. Even in 2002 and 2005, when Al Qaedah-linked jihadis targeted Bali in a series of deadly bombings, no open conflict occurred. The leaders of the local Moslem minority quickly closed ranks with their Hindu brothers. Peace continued prevailing.

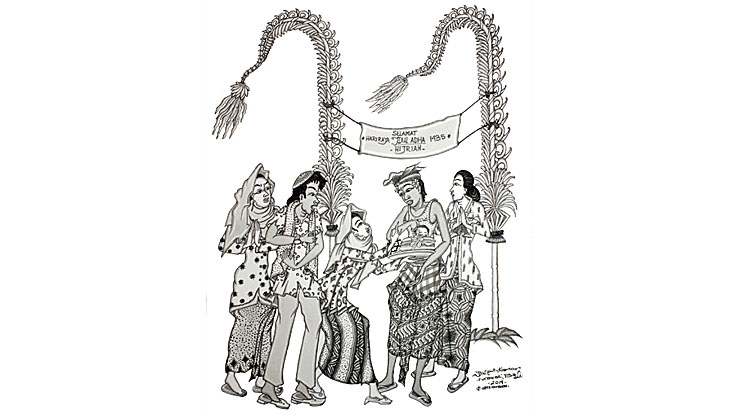

Yet, nothing should be taken for granted. It would be a mistake to think that past historical tolerance ensures tolerance in the future. Why? Because some important, cumulative changes are taking place, which, if not properly handled, can damage traditional harmony. The main change is demographic. Non-Balinese migrant workers are settling in Bali in ever bigger numbers. Not only do they give job competition an ethno-religious hue, but, more seriously, some of them bring along a more narrow interpretation of holy texts that tend to reinforce socio-religious identity and thus increasingly separate Moslems from their Balinese brothers and sister. For example, it was relatively common, until twenty years ago, to perform Balinese dances at Moslem circumcisions and weddings. Upon advice from orthodox clerics, it is now considered improper as Balinese dances are usually accompanied by offerings.

Similarly some Islamo-Balinese youths educated in Javanese religious institutions come back to Bali upon completion of their studies convinced that the genuine followers of the prophet should refrain from participating in Balinese religious rites. As for inter-religious marriages, they are becoming rarer because deemed contrary to the religious precepts.

The pervading influence of Wahabism in Indonesia has been central to these social changes. So, the traditional advocacy for Moslem tolerance, rooted in the sentence, “Your religion is your religion, my religion is my religion,” is now given a narrower meaning. Instead of being interpreted as an acceptance of difference between religions, it now commonly understood by Balinese Moslems as an advocacy to eradicate from their tradition all elements deemed tarnished by Hindu influences. As a result, Hindu-Balinese and Moslem-Balinese, who were for centuries virtually undistinguishable from one another with regard to social behaviour and identity, increasingly see themselves – and are constructed by others – as belonging to distinct and contrasted communities. Previously mixed and mixing, there is now an increased separation, because Hindu-hood and Islam-hood are construed as identity markers more important than their shared Balinese-hood.

The Hindu-Balinese do experience their own revivalism and crystallisation of ethno-religious identity, rooted not so much in a reinterpretation of the holy Hindu scriptures than as a reaction against socio-economic and cultural changes, topped by a tourism-induced idealisation of “tradition”. Ethno-centrism is visible in almost all walks. , and little is done to counter it.

What took place in my village, Abian Gombal, a couple of years ago, illustrates the complexity of the issue.

The village has a small Moslem minority, most of whose members work at a local agricultural company. They had a small, unregistered prayer room within the premises of the factory. One day, while bathing there, the young child of one of the workers was swept by the flooding waters and drowned. His corpse was then for some reason taken to the prayer house before being sent to the Moslem cemetery for burial. To a non-Balinese outsider, there was nothing extraordinary in this handling of what looked like a personal tragedy. But to Hindu and Moslem revivalists alike, it opened Pandora’s Box: to the local villagers, the fact of keeping a corpse outside a place attributed to the rites of death (cemetery or family compound) brought impurity to the village — this could in turn cause other woes like accidents or illness to run rampant. Therefore the village had to be cleansed by a Rsi Gana exorcism.

Who should pay for it? To the locals, it should be paid by those who had, albeit unwittingly, caused this “impurity” to occur: the Moslems. The latter, however, would not do it, because this would violate the Sharia prohibition to participate in non-Moslem rites. A vicious cycle indeed! It is at this point that real tensions could have occurred. But luckily, the local elders and the factory owner found a way that cooled down the tempers: it was decided that the Moslem prayer house would be closed for ten years. It was discriminative, yes, but it was also a way out.

This example shows that tolerance is not simply a matter of good will. It has to be properly “managed” at the grass root level. In the end, the future of tolerance in Indonesia depends not only on lofty abstract principles, but also on our awareness of the social issues that arise as the result of economic and cultural transformations. Indonesia is an officially multi-religious state. Its ulema clerics have been enlightened to the point to grant to Balinese Hinduism the status of religion of the book. But tolerance has to be upheld every day, not only in society at large, but also in our own heads.

Wishing you a peaceful, tolerant and reflective Ramadan.