For more than three decades, Ashley Bickerton’s presence shone brightly on the international art stage. A courageous, rebellious artist, his genius imagination existed on the periphery of what was conceivably possible. Bickerton rose to incredible heights in contemporary art, positioning his voice as singular to the global audience.

The most internationally renowned contemporary artist in Indonesia, he was loved and admired by many. After more than a year of battling ALS, a debilitating motor-neuron condition known as Lou Gehrig’s disease that severely limited his physical activities, Bickerton passed away peacefully on 30 November 2022 on the Bukit peninsula of southern Bali. He was 63 years old. In the following days, his achievements were honoured in the international art world news media.

Born on the island of Barbados in 1959, Bickerton grew up living in various countries. His father was an anthropological linguist, and his mother was a behavioural psychologist. Uprooting regularly, he spent time in South America and Africa. His family moved from Guyana to Ghana, England to the U.S., settling in Honolulu, Hawaii. Often he and his brother were the only white children at the schools they attended. As an outsider, he observed the dynamic environment around him on multiple levels through the eyes of a global citizen.

During the mid-1980s, Bickerton shot to fame, becoming a market sensation upon the world’s premiere art stage in New York. He featured alongside his compatriots Peter Halley, Meyer Vaisman, and Jeff Koons in the famed and critically applauded 1986 exhibition at Sonnabend Gallery. The four represented part of the East Village’s Neo-Geo movement, which emerged in response to the growing industrialisation and commercialism of the modern world. They revived geometric abstraction with new postmodern affiliations.

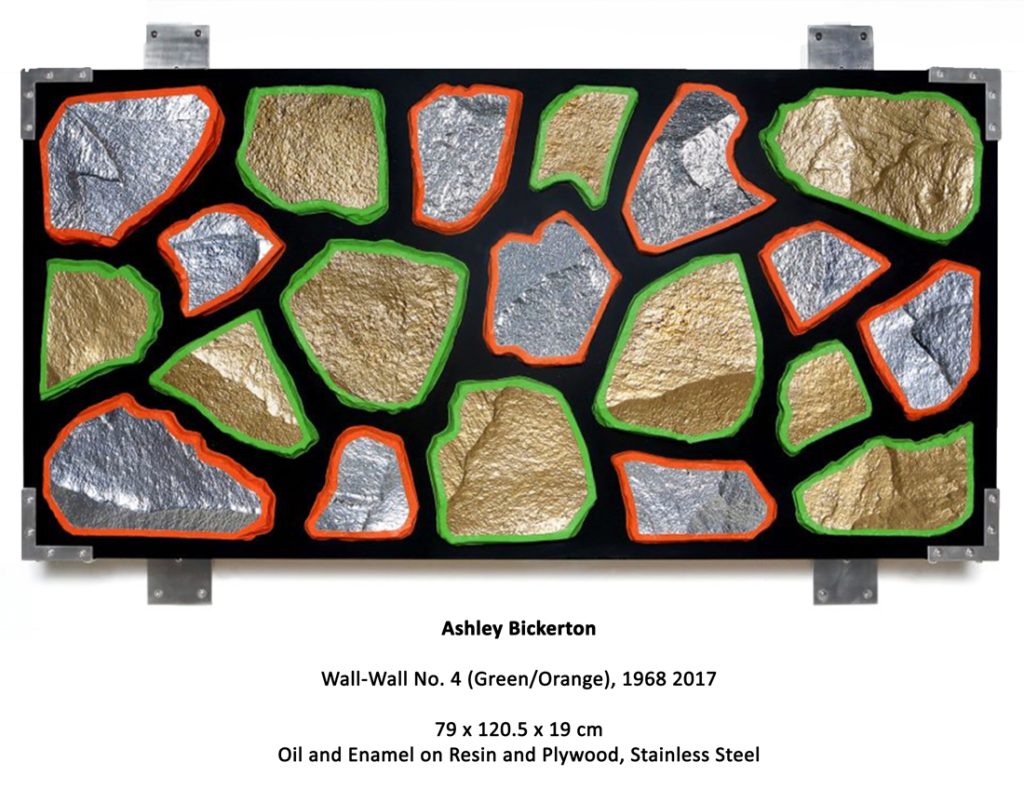

Bickerton consolidated his name in the 1990s with self-portraits that lampooned the consumer world. He labelled the highly stylised 3D objects, boxes adorned with international titan brand logos “contemplative wall units”. From there, Bickerton’s continued to evolve and he ventured into territories challenging to describe. Metal assemblages affixed with elements like leather coverings and polished aluminium pieces, some objects appeared like time capsules or floatation devices that had just rolled off the assembly line.

In 1993, Bickerton turned his back on the art metropolis and relocated half way around the world to exotic Bali. An avid surfer, Bickerton had an infinity with mother nature. Now liberated from the pressures of the art world he knew too well, he initiated a new and reinvigorated creative era.

A master technician, Bickerton was equally adept at creating both two and three-dimensional mixed media works. He merged his slick conceptual roots anchored in New York with his vibrant tropical oceanic influences. He shifted between two visual languages, one a modernist, minimalist abstract aesthetic, the other with unbridled expressionist flare fusing the beautiful with the macabre, blurring the boundaries between good and poor taste. Prolific and innovative his acute ability was to respond to the chaotic times that we live in.

Highly articulate, Bickerton was a good self-promoter however, institutional support and validation for his art was he saw as lacking, once commenting, “but I don’t get institutional support. I’ve never had one regional kunsthalle or one university museum, let alone a one-person museum show of any sort—nothing.” An art journalist noted “this absence of a desire on the part of critics and academics to really grapple with the deeper critical meanings of your work.” However, in recent years, thanks to significant galleries such as Lehmann Maupin and Gagosian, principal artists like Damien Hirst and Jordan Wolfson Bickerton’s work enjoyed a critical revival.

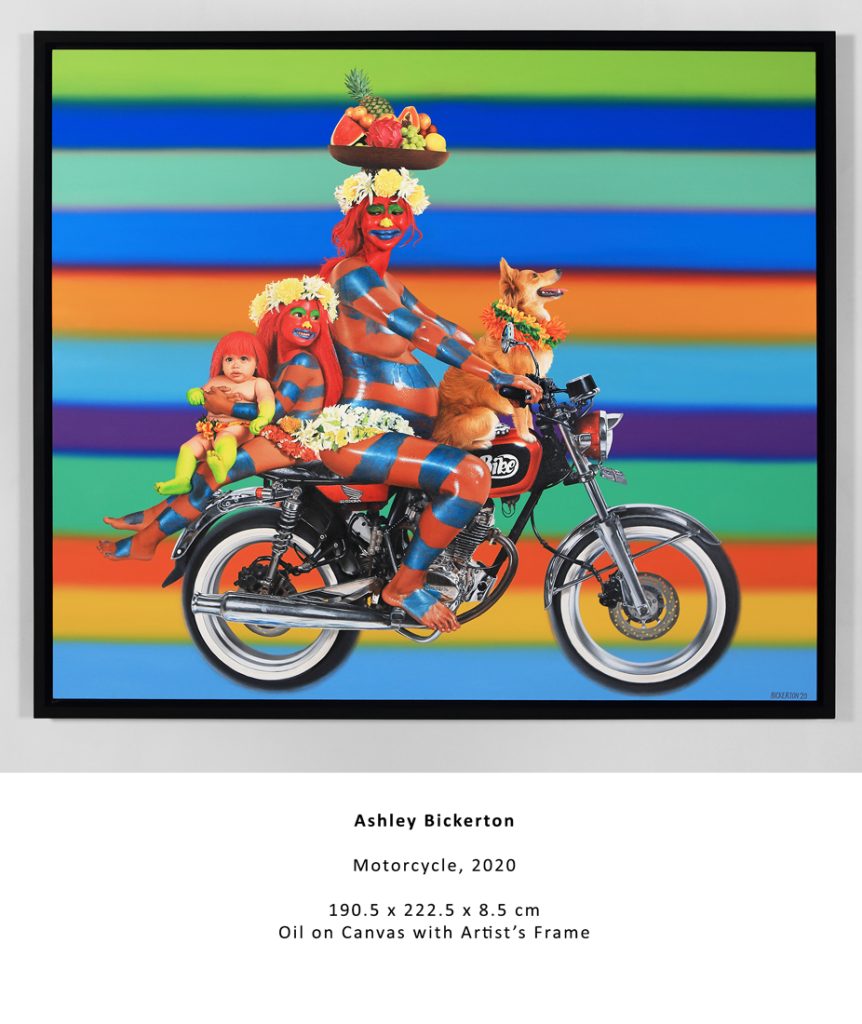

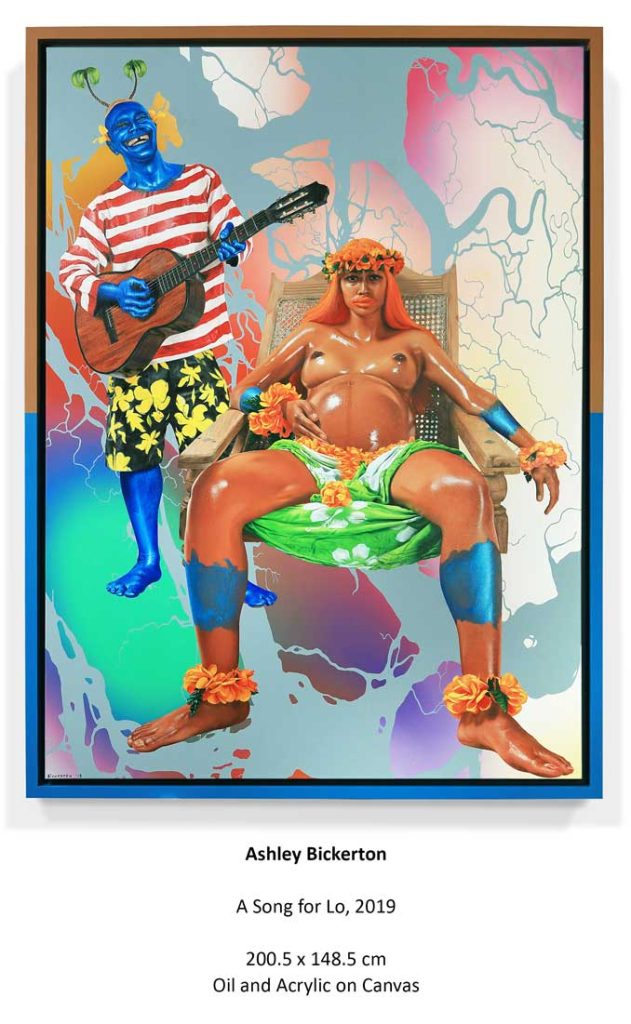

Post-colonial concepts were a central focus. He criticised the Bali tourism industry with sharp, satirical observations of the dilution and transformation of a remote island to an international tourist destination. He created beguiling, vibrant images of the white male tropical experience emphasising decadent neo-colonial behaviour. Bickerton imagined foreign visitors as super-sized, blue creatures that ride mopeds with swathes of bikini-clad local women. He often included his own parodied image as the protagonist.

His complex paintings were layered with numerous photographed images photoshopped and then printed onto canvas, upon which he painted and added sculptural mediums. Bickerton described these works as parodies of paintings, “I never saw them as real paintings, but as jokes,” he stated. Labelled a modern-day Paul Gauguin, he inevitably could not escape the association, so he played the role to its utmost, accentuating the ugly extremes of modern western ideals in the tropics. “A big part of my life has been trying to reconcile those two worlds” (New York and Bali), Bickerton once said in a recent interview

The ubiquitous trash that litters Bali beaches in the form of plastic flotsam and jetsam he transformed into visual poetry inside boxes with mirror rear panels so the observer’s image becomes a part of the artwork. He cast sharks in bronze, transforming the fearsome creatures into majestic totemic embodiments. Bickerton continued working throughout his illness. The Gagosian gallery is planning to showcase some of his final creations during 2023.

Bickerton’s works reside in numerous public and private collections internationally including the Museum of Modern Art (New York), Whitney Museum of American Art (New York), The Broad (Los Angeles), Tate Britain (London), Stedelijk Museum (Amsterdam), Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Donnaregina (Italy), Museu Colecão Berardo (Lisbon), Hara Museum of Contemporary Art (Tokyo, Japan), among others.

Ashley personified the human essence that we are born as creators, each with enormous potential. In becoming an open channel for the universal life force, he lived a whole and empowered existence that inspired others to live beyond their limitations. His legacy is recorded as a unique stimulus for many, especially the younger generations. He is survived by his Balinese wife, Cherry Bickerton, and his three children. Rest In Peace, Ashley; you are greatly missed.